Game design is all about the rules, gameplay and player experience and emotion within a game. Game design is not gamification which is about using elements such as point scoring, competing with others and rewards to make a product or learning more engaging. While gamification elements are incorporated into game design they should be part of it rather than used alone.

Game designer and developer Robert Zubek defines game design in his book Elements of Game Design by breaking it down to its elements, which he says are the following:

- Mechanics and systems, which are the rules and objects in the game (environment and toys)

- Gameplay, which is the interaction between the player and the mechanics and systems (goals and controls)

- Player experience, which is how users feel when they’re playing the game (emotions and flow)

Mechanics and Systems

When considering game design for learning it is important that the game mechanics are relevant to the learner, the rules clear and the way they interact with the game easy and obvious.

The objects or "toys" within a game should be fun and playful and the learner should never become frustrated with the rules of the game or the way they interact with the game. Actions should be obvious and easy and feedback should be clear and concise to help the learner improve.

Consider how you are currently learning. Is it fun highlighting notes? Is it obvious what you don't know and need to learn? Is any feedback or challenge being provided?

Importantly the environment the learner is placed in needs to be safe and enjoyable and conducive to learning and growth.

To illustrate these point in 2017 Mark Rober a former NASA and Apple engineer and a YouTuber with more than 15 million subscribers asked his YouTube followers to play a simple computer programming puzzle that he made with a friend. The object of the puzzle was simple and clear — to get the car across the maze by arranging the code blocks that represent typical computer programming operations. This was relevant to his audience, was playful and was easy to access with a challenge and clear goal.

What the 50,000 followers who took part didn’t know was that Mark randomly served up two different types of game.

In one version, if you hit run and weren’t successful, you didn’t lose any of the starting 200 points and were shown the message: “That didn’t work. Please try again.” However, if you hit run in the second version and weren’t successful, the program showed a slightly different message: “That didn’t work. You lost 5 points. You now have 195 points. Please try again.”

The difference between those two messages revealed something very significant about the human psyche through the results of the test.

68% of the people who didn’t lose any points ultimately solved the puzzle yet only 52% of the people who lost 5 points were able to solve the puzzle. That’s a delta of 16%! Another piece of data Mark collected was how many tries the players took before they gave up. The group that didn’t lose any points averaged at about 12 tries, while people who lost 5 points, averaged at about 5 tries.

The group that made more attempts saw higher success rates than the ones that made fewer attempts. The difference between the two groups stemmed from the different messages they were shown on failing. Mark termed the results of the experiment The Super Mario Effect:

“When it comes to games like this, no one ever picks up the controller for the first time and after jumping into a pit, thinks — I’m so ashamed. That was such a failure — and they never want to try again. That doesn’t happen. What really happens is they remember that there’s a pit right there and their job becomes to not fall into the pit again. While playing a game, we learn from the failures but don’t focus on the failures."

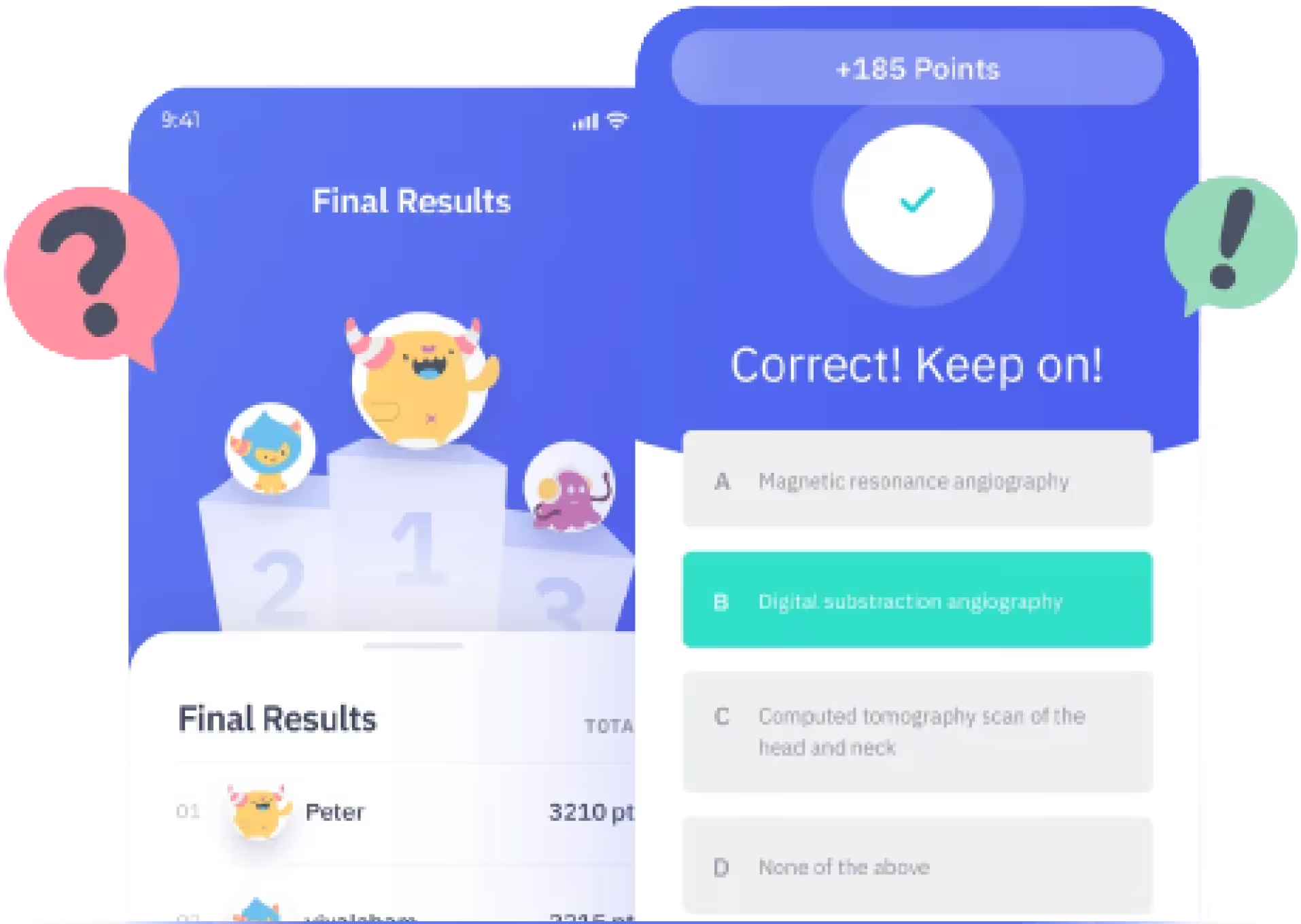

Gamification elements can be considered toys and part of game mechanics. In learning, elements such as leaderboards, points and streaks can be employed effectively to motivate the learner to beat their own previous score or streak and/or the score or streak of others. These elements assist users with goal setting, boost competition, and provide feedback. Leaderboards should be designed such that they are relevant and compare learners with peers of the same skill level and time period spent learning such that learners are not demotivated by perceived poor performance. A 2021 study by Park et al suggests combing macro leaderboards for overall score with micro leaderboards related to learner activities, often defined as badges or achievements. The study highlighted Khan Academy, Reebok Crossfit and Pokemon Go's leaderboards as being good models to replicate.

Game mechanics and systems should provide the learner with clear rules and fun toys to interact with. They should support failure and encouraged attempts and be directly relevant to the learner and their learning goals.

Gameplay and Controls

Designing gameplay well is considered by researchers to be crucial for effective game design. Gameplay consists of:

- goals for players to achieve;

- non-trivial challenges that players overcome in order to accomplish those goals;

- actions that players perform to overcome those challenges;

- choices that players make about what action to perform and when to perform it

Controls are how the learner interacts with the game and the feedback they receive. Think of a fighting game like Street Fighter. Similar to a real martial art the button combos are challenging to learn but players are motivated to do so in the short term by the visual feedback of the move successfully performed and the bigger challenge of beating their opponent. Challenge increases when moves must be linked together and performed under pressure while taking into account the position and moves of the opponent character.

Micro-interactions are an example of immediate playful and positive feedback that can be incorporated into digital products and make seemingly boring interactions fun and playful. By simply changing how a click interaction is displayed the user is delighted with a feeling of joy and surprise since the interaction exceeded what they would usually expect to happen when pressing a button.

In learning and studying setting clear goals such as being able to actively recall a topic or get a test question correct offer a non-trivial challenge combined with defined actions (practise x number of questions per day) to get there. This is in contrast to simply passively reading a book which other than completion offers little challenge.

In terms of controls writing notes by hand or creating flashcards or visual diagrams to test knowledge is sometimes preferred by learners due to the kinesthetic and visual feedback offer by the creation process. For digital studying systems which allow for daily goals and challenges intrinsically challenge players when combined with social proof challenges such as leaderboards and analytics such that the learner can compete against both themselves and their peers. Digital products should allow for fast learning with intuitive controls such as being able to quickly select answers and receive immediate clear feedback without the need for multiple logins or preamble.

Learner Experience and Flow State

If you have read Hooked by Nir Eyal you'll know that psychology is a huge part of game design and to form a habit a person needs to receive a trigger, perform an easy to complete action, receive a variable reward that relates to the trigger and then must invest time in the experience to form a habit where the trigger to take action is no longer external (such as a calendar reminder) but comes from their internal motivation. Emotion plays a huge role in game design with the goal to delight the user and make the experience enjoyable. The body's physiological reward response is to release dopamine giving you that feeling of joy. Studies have shown that our craving for rewards causes a stronger emotional reaction than receiving the reward itself and games will often employ variable reward mechanics such as loot crates and random results to engage players. As Nir says in his book it is important to use habit formation responsibly and build products which are helpful and not detrimentally addictive.

In the 1970s Psychologists Mark R. Lepper and David Greene from Stanford and the University of Michigan were interested in testing what is known as the ‘overjustification’ hypothesis.

Since parents so often use rewards as motivators for children they recruited fifty-one preschoolers aged between 3 and 4. All the children selected for the study were interested in drawing. It was crucial that they already liked drawing because Lepper and Greene wanted to see what effect rewards would have when children were already fond of the activity.

The children were then randomly assigned to one of the following conditions:

- Expected reward. In this condition children were told they would get a certificate with a gold seal and ribbon if they took part.

- Surprise reward. In this condition children would receive the same reward as above but, crucially, weren’t told about it until after the drawing activity was finished.

- No reward. Children in this condition expected no reward, and didn’t receive one.

Each child was invited into a separate room to draw for 6 minutes then afterwards either given their reward or not depending on the condition. Then, over the next few days, the children were watched through one-way mirrors to see how much they would continue drawing of their own accord. The graph below shows the percentage of time they spent drawing by experimental condition:

As you can see the expected reward had decreased the amount of spontaneous interest the children took in drawing. So, those who had previously liked drawing were less motivated once they expected to be rewarded for the activity. In fact the expected reward reduced the amount of spontaneous drawing the children did by half. Not only this, but judges rated the pictures drawn by the children expecting a reward as less aesthetically pleasing.

For game design and learning we want the learner to enter a flow state in which they can derive great joy from a learning activity.

Flow is a state of optimal experience and intrinsic motivation, available to any person regardless of age, gender, or cultural background. The main criterion for creating the flow experience in a game is to have a balance between the difficulty of tasks for players to accomplish, and the level of their ability or skill to accomplish those tasks. Tasks that are too difficult for players to perform will result in frustration. Tasks that are too easy will require little effort, and thus result in boredom. In both cases, players lose their motivation to play the game.

Determining whether the difficulty of any task is appropriate depends on the skill of the player. A player's skill may increase as he or she progresses through the game. Thus to maintain flow, game and learning designers need to ensure two things: firstly, that the difficulty of tasks increases as players progress through the game; and secondly, that the players' skill remains balanced with the difficulty of tasks.

How You Can Employ Game Design To Learn Faster and Stay Motivated

While a lot of what we have discussed has been game design theory there are some key simple concepts that you can add into your own learning practise as a student, learner or teacher:

Use fun toys and your own learning mechanics:

Decide how you are going to learn. We have already seen that active recall and spaced repetition offer the quickest ways to learn and choosing whether you are going to use a digital study tool or create your own written note cards and quizzes is effectively you being a game designer and selecting your toys or objects to interact with before you start. Ensuring you adopt a growth mindset and learn from failure through active recall and testing is also part of setting your environment for success. Embracing incorrect answers and failure to recall on the first attempt but continuing to do so is The Super Mario Effect in action.

Set Your Goals and Controls

Creating a curriculum or study timetable that challenges and rewards you and tests more advances, applied knowledge as you learn will keep you interested, motivated and satiated with learning challenges. This might simply be taking a time mock test at a set time in your study timetable or having a peer quiz you under social pressure and mixing up your revision styles. Feedback and variable rewards after interacting with your study materials will also help you to stay motivated. This can be as simple as rewarding yourself with a random gift or taking a fun break or reflecting on what you have learned.

Flow State and Habit

Make your learning and studying easy to get you into a flow state by removing any barriers and ensuring that you:

- Know what to do next

- Know how to do it, and

- Are free from distractions

- You must get clear and immediate feedback

- And you must feel a balance between challenge and skill.

A great way to do this is to set reminders (external triggers initially) to study for a set period of time at the same time each day. Having your study area prepared and laid out and the topics you will be studying and the method for studying prepared the night before means that you can immediately dive into studying with minimal resistance. You should plan to use active recall and testing to receive immediate feedback and plan topics that you have not yet mastered or set realistic goals that challenge you for the study session such as applying knowledge.

How We Use Game Design At Shiken

At Shiken everything our product team has created follows theses principles. From the fun, playful study buddies who guide you through the experience to the goals and reminder notifications system that helps you to study using bite-size goals and master a revision product entirely. Variable rewards can be seen in the accessory and buddy unlock mechanisms and microinteractions such as the music and celebration animations deliver delightful feedback. The questions system itself is the perfect example with daily streaks and challenges encouraging consistency and the system itself designed to be fast and to provide immediate feedback and detailed analytics to help you actively recall information and test and challenge yourself.